Image: “The Garden of Eden with the Fall of Man” by Jan Brueghel the Elder and Pieter Paul Rubens (1615).

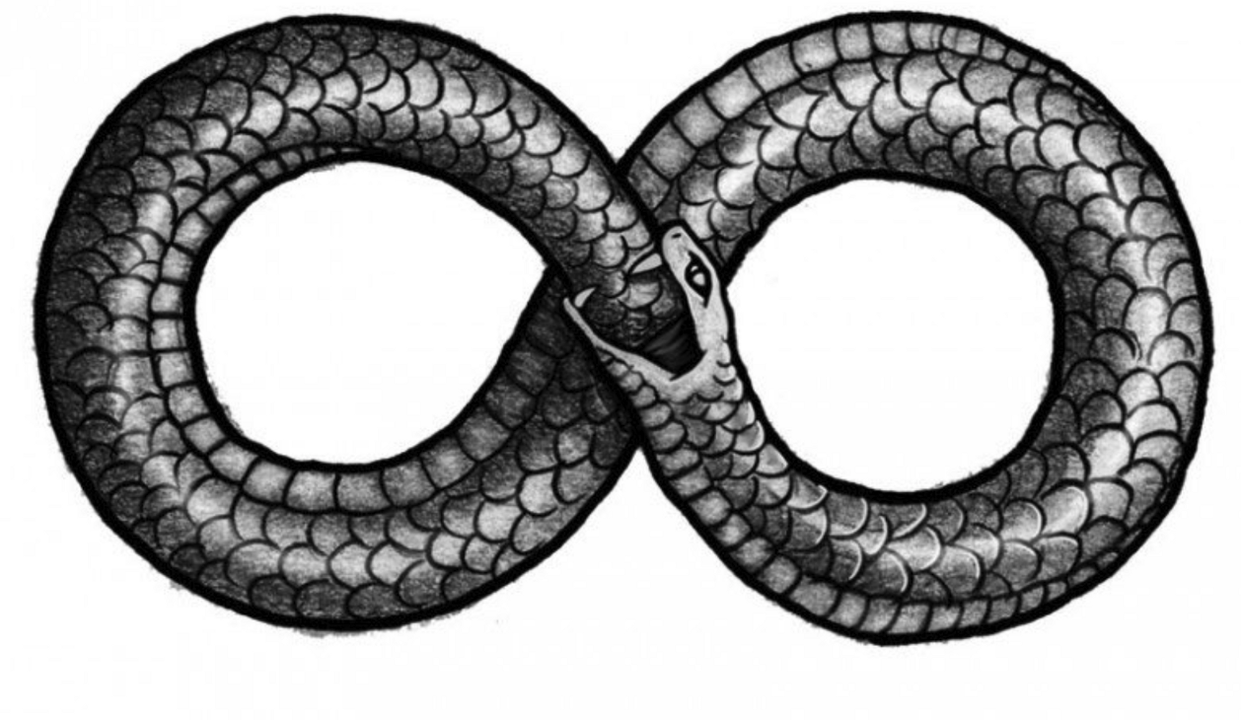

In the beginning, mankind’s transformation of the Earth may have been set into motion by a single word, and the word was that man should go “subdue” the planet.

As the Book of Genesis reads, “God made the wild animals according to their kinds…And God saw that it was good. Then God said, ‘Let us make mankind in our image, in our likeness, so that they may rule over the fish in the sea and the birds in the sky, over the livestock and all the wild animals,[a] and over all the creatures that move along the ground.’ God created mankind in his own image…blessed them and said to them, ‘Be fruitful and increase in number; fill the earth and subdue it; and have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the air and over every living thing that moves upon the surface of the Earth’” (Genesis 1: 25, 26, and 28).

Subdue means to “overcome, quieten, or bring under control” (Google). Nature, the Bible seems to imply, was somehow too wild and out of control in the early days of creation. A few verses later, it tells the story of how God placed man in the Garden of Eden and expected him to “work” and “take care” of it (Genesis 2: 15). We can imply that Adam was supposed to keep God’s creation quiet and manageable in his subduction of it.

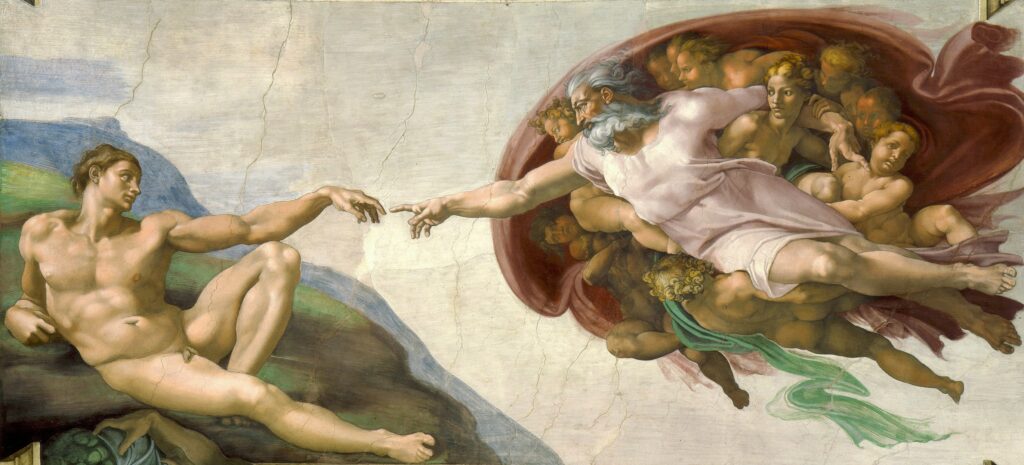

Image: “The Creation of Adam” by Michelangelo (1512).

Fast-forward six to ten thousand years (according to young Earth creationists) and around three hundred thousand (according to science) and many of the Earth’s natural systems are caught up in a wildfire of change so rapid or deafening that’s its simply unmanageable for many species. In the tropics, countless trees, typically very specialized amidst fierce competition, can’t seem to keep up with the pace at which climate change is shifting the special temperatures they require uphill (Kolbert, 154-59). More broadly, sufficient rains only blanket Earth’s most essential albeit savage Eden—the Amazon rainforest—because its trees contribute moisture in their leaves to the atmosphere overhead. Sometime in the 2030s, the forest will have simply lost too much of its rain-generating power to go on. It will cement its transition to savanna.

On the other side of the America’s, the forests of Yellowstone National Park and other protected areas likewise have a precarious future. Pastoralists, interested in protecting their livestock (or simply in extracting revenge), are ruthlessly hunting down grey wolves that have wandered beyond the borders of protected areas. At current death rates, the wolves of Yellowstone won’t survive many more generations (Williams, 2022). And without wolves, the park’s young generations of trees (lest us modern Adams forget the value of national parks and turn the last remnants of largely intact creation into a hunting ground) will lack the protection they need against out-of-control herbivore populations. In a word, Yellowstone will be doomed by us humans far before that supervolcano can do the job!

Add in the series of global carbon bombs and countless other aspects of the global environmental crisis, and no matter how hard we put our God-given brains to use, quite contrary to the apparent wishes of the Lord and the advice of most secular scientists, the current environmental situation is quite outside of man’s control. Modern man has clearly overstepped his biblical mandate. The decedents of Adam, it seems, have outright fallen on the job. We’ve lost our ability to lovingly subdue a system that (if you believe the Bible) we were entrusted to steward.

Image: “The Temptation In the Wilderness” by John Saint John Long (1824).

Throughout history, Christianity has generally promoted notions that the wilderness and the world at large are untamed and even evil theaters where people can meet God but also be tempted by the Devil (Stankey, 9-14). In the eyes of many a theologian, mankind was expected to exert his dominion over a potentially terrible, wild world, and this generally meant transforming its character into a tame, moral one pleasing to God. Wolves and other wild creatures that might prey upon the sacred flock were exterminated in mass. The world was to be filled with pastureland and sheep destined for eternal life, as in Jesus’ parables, but also habitat loss on account of pasture clearing and persecution of keystone species, cutting the life of the world short.

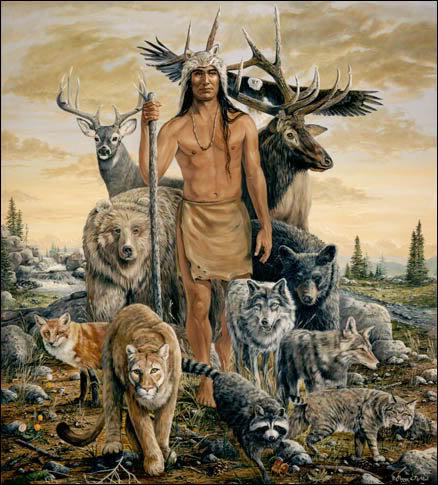

Upon arrival in the Americas, Christians probably thought the natives’ spiritual practices rhymed with the old pagan animism they had rejected in favor of the governance of the one God. Museum artefacts help us understand the details of these practices. The guide to the New York Museum of the American Indian indicates that “the Central Algonkians, like many other Indians, believed in a multiplicity of spirits, whose abiding places were in some cases above, and in others below, the earth, and whose chief was a great spirit, who in some cases, at least, was thought to be the sun. According to tradition, these spirits granted visions to the Indians, in which they were instructed how to prepare the sacred bundles (of which several are exhibited), containing charms, medicines, and ceremonial regalia, supposed to have the power of bringing good health and success in all the affairs of life” (Indian Notes and Monographs, 35). The Algonkians of Eastern Canada, moreover, believed that the souls of animals surrendered themselves to an Indian hunter after he or she consulted his or her soul-spirit in a dream (Richards, 472). The hunter’s soul-spirit would be in contact with animals’ and need to receive permission from an animal’s soul to slay it (Richards, 472).

For Christians, again, this likely smelled of polytheism. Concerning relationships with other aspects of their natural environment, Christians, moreover, did not typically believe that they had guardians or feelings (as they often did in the old pagan animist belief systems), so that the feelings and protection of such features could be disregarded (Attfield, pp. 370). In a word, beyond the heart of Saint Frances, there appears to be little to no awareness of responsibility and accountability toward nature in most of historical Christendom’s relationship with tree, forest, and other things inhuman. This way was quite in contrast to that of the Algonkians and Indians more broadly. Historical Christendom, though it strives to return to paradise, apparently forgot that by biblical accounts it fell from an original Arcadia full of trees, and, furthermore, that it is expected to be a caretaker of creation.

Many European colonialists looked at the native peoples of the New World as lost souls. Worse, as souls lost in the untamed wildernesses of an ungraced continent!

As one Jesuit missionary put it his account of events, “But as to the new world, discovered some hundred and twenty years ago, we have no proof that the word of God has ever been proclaimed there prior to these later times; unless we are to believe the story of Jean de Lery, who says that one day as he was telling the Brazilians about the great miracles of our redemption, an old man told him that…many years before a bearded man…had come among them and had related something similar; but that they would not listen to him, and since then had been killing and eating each other…It remains now to deplore the wretched condition of these people” (Poutrincourt, The Jesuit Relations, 59 and 61).

Another Jesuit missionary to New France describes the situation ahead of him with apparent disdain as his ship nears the New World, chronicling that “we were going into a dreary wilderness” (Biard, The Jesuit Relations, 137). “Nothing fouler and more hideous than the savage Canadians could have been imagined, before they began to soften under the influence of religion, as will appear from matters to be presented in the tenth Paragraph. Now, barbarism and the vile array of sins have given place to reason and virtue, which seems to confirm our faith in this ancient prophecy: The land that was desolate and impassable shall be glad, and the wilderness shall rejoice, and shall flourish like the lily” (An Account of the Canadian Mission, 205). This last account of the Jesuits’ first mission to New France in the early Seventeenth Century drives the prevailing perspective of the Jesuit missionaries to New France home. Apparently, largely forested New France was a “desolate” wilderness.

Image: “Father Marquette and the Indians” by Wilhelm Alfred Lamprecht (1869).

Of course, there were individuals among the Jesuit missionaries who went against the grain of the more common Christian attitudes toward nature and wilderness in the time of New World colonization. Consider the writings of Father Chrestien Le Clercq, who labored for nearly twelve years as a late Seventeenth Century Jesuit missionary to the tribes of the Canadian provinces. “[The Indians],” Le Clercq writes, “have believed that this luminous planet, which, by its wonderful power and its marvellous effects, constitutes the adornment and all the beauty of nature, was also the first author thereof, and that therefore they were obliged, out of gratitude, to hold all the sentiments of respect of which they were capable for a planet which did them so much good by its presence, and whose absence, during the darkness of the night, brought mourning to all nature” (Le Clercq, 157). Le Clercq is a man with a clear respect and joy for the planet he views as God’s creation.

Nevertheless, even by Le Clercq, it remained paramount that the Native Americans be made pure and holy, separated from the sin within their own nature and that of the wild, wild Earth.

Unfortunately, most of the Native Americans were not brought into the life of a graced continent (at least not before most of them were destroyed). It is a vast and tragic tale, that of the fall of Native American peoples in the age of European colonization and westward conquest. It is also one that reflects our situation today, concerning a civilization essentially destroying the planetary system upon which it relies for subsistence.

According to historian John F. Richards, European contact with the New World brought rapid commercialization of human predation across the Atlantic in the form of the fur trade. Let’s go over how it evolved.

Native Americans had superior hunting and trapping skills as well as access to better hunting grounds (Richards, 474). What is more, the Indians were willing to trade furs for inexpensive goods (Richards, 474). Europeans, meanwhile, generally had little interest in rigorous hunting and trapping (Richards, 474).

European capitalists thus had great economic incentive to push involvement in the trade upon Native Americans. It is also clear that many Indians took the Europeans’ offer. Richards argues that Algonkian culture became dependent on French trade goods with tools of stone and wood replaced by ones of iron, bows and arrows by pistols, and deer skins and beaver robes by shirts and blankets (Richards, 474).

What is more, Indian hunters began asserting private property rights over their hunting territories (Richards, 474), quite contrary to traditional beliefs that natural elements and animals essentially had rights and were no one’s property prior to consent. These hunters and trappers also dealt with European traders increasingly on an individual basis not accountable to the head of the Native American hunting bands—and, by extension, to the interests of the larger tribe (Richards, 473).

Overhunting of traditional grounds and game scarcity resulted, and soon only the most skilled individual hunters could be relied upon to bring in furs (Richards, 473).

The vicious cycle of overhunting became even more unchecked by the interests of the tribes at large. By the mid-Seventeenth Century, beavers and other furbearers were scarce in eastern Algonkian territory (Richards, 473). Indian cultures that relied upon mammalian game for meat and clothing (or to trade for it and other valuable goods) were out of luck. There traditional economy, social structures, and spiritual practices were in shambles. If they had a near-term spiritual future in a more Europeaneque North America, there was certainly not one for them in commerce since they had left themselves with little to nothing to trade!

Image: Photograph of a fur trader in the Northwest Territories.

It is hard to imagine the Indian trappers and hunters who were bringing in large numbers of dead game in the fur trade taking the time to consult dreams prior to every kill. Undeniably, part of northeastern Native American’s destruction was indeed self-inflicted by the consequences of a shift in their cultures away from traditional beliefs and practices concerning humanity’s relationship with nature. They moved toward the time’s typical exploitative European attitude toward the Earth and its resources.

Due to the possibility that Seventeenth Century destruction of Canadian ecosystems was largely driven by individual hunters and trappers, however, it is unclear how much blame the Seventeenth Century Native Americans of Canada and what is now the northern United States at large deserve in their societies’ decline.

It is true that the turn to a more European attitude toward nature amongst such peoples was heavily influenced by what Europeans brought, namely the temptations of their material culture, pressure to compete technologically with an invading foreign power, disease, and a kind of perfect storm of disillusionment with nature and traditional practices in its aftermath. On top of that, the Indians’ cultural falling out was accompanied by Native American attraction to a hierarchical spiritual and social order that claimed to protect people in a threatening world. It involved a great enough portion of the Indians to undermine resistance to the individual hunters and trappers responsible for the bulk of the fur trade and its consequences for northeastern Native American societies.

Indeed, Calvin Martin, in his book Keepers of the Game: Indian-Animal Relationships and the Fur Trade, postulates that the Native American trappers and hunters of the fur trade surely knew that their “subsistence economy was underpinned by a reliance upon fish, game, wild plant foods, and, in some cases, cultivated plants” but seemed “oblivious to wildlife population dynamics” (Martin, 3).

There was not, however, ignorance throughout Indian communities of the Seventeenth Century regarding what was being done to wildlife populations. For Martin notes that multiple fur company agents and missionaries recorded instances of lament among the Indians anticipating the disaster that overhunting would bring (Martin, 3). He suggests that these Native Americans driven by such concerns were simply not the majority (Martin, 3). “Presented with the opportunity to exchange their pelts and skins for European trade goods,” Indians “quickly seized the opportunity to effect the transaction” (Martin, 8).

Martin ponders whether Seventeenth Century Native Americans’ embrace of the fur trade has a purely materialistic explanation. He believes Indians saw the superior value of European technology and material culture—as well as the threat inherent in not acquiring it in a competitive world—and were willing to overkill numerous animals to improve their condition, or simply to survive (Martin, 8). Martin also holds that the lack of reservation amongst the Native Americans in the fur trade when it came to driving many species to the brink of extinction stemmed from disillusionment with nature in the aftermath of rampant sickness. With their traditional religious belief in a Great Spirit and practices to ensure harmony with the natural world, many Native Americans simply felt betrayed when European-borne pathogens nearly wiped them out (Martin, 1). Thus, they had few reservations in the hunting of many animals because of a perceived betrayal by nature, with their spiritual practices should have guarded against (Martin, 1).

This hypothesis seems highly plausible when we consider just how widespread disease was amongst the Indians of northeastern North America. American physiologist and demographist Sherburne Cook showed that from 1620 to 1720 (that is, starting several decades before the devastation of the eastern Canadian mammalian populations climaxed) four fifths of New England Indian populations were likely eliminated by disease (Martin, 46). It is quite conceivable that such a massive societal catastrophe had a significant impact on Native American minds.

Nevertheless, this happened over the course of a hundred years, and Canadian game mammals were scarcely found only thirty years into this period. If the experience of disease did shift northeastern Native American views of nature, it probably did not do so abruptly nor as a singular factor.

This post holds that the transformation of Native American values did not coincide seamlessly with the Seventeenth Century collapse of furbearer populations in Canadian ecosystems; rather, that any revolution in values lagged behind the collapse of ecosystems. We can determine just how large a role disease and materialistic motivations had in the evolution of northeastern Native American attitudes toward nature by dismissing other possible causes for such change.

Was Native American spirituality fertile ground for the adoption of the Christian idea of a high god/God and worldview before any factors such as the disenchanting influence of disease were relevant?

Jordan Paper’s essay The Post-Contact Origin of an American Indian High God: The Suppression of Feminine Spirituality illuminates the nature of the transition of Indian beliefs to incorporate a single high god and how Europeans shifted Native Americans’ religion away from a deification of nature. As Paper tells it, Europeans converted the Indians of New France to an attitude that embraced social hierarchy and divinity that was no longer one with nature. Conceivably, Native American attitudes shifted on whether they owed respect to animals, specifically on the question of asking permission to kill wildlife for food or furs (Paper, 1). There are different perspectives on whether the Native American high god was part of a “primitive monotheism” (Paper, 1). “The Great Spirit” was an “erroneous interpretation” of the Siouan term “Wakanda” and the Algonkian “Menomini” (Paper, 1). Paper notes that it was mainly through the influence of missionaries that “Wakanda” was interpreted as a supreme being (Paper, 1). He suggests that the high God concept emerged in Native American cultures only after conversion to a new consciousness that included awareness of a European hierarchical social structure under a supreme ruler (Paper, 2); the traditional religion of the Indians of northeastern North America was not so inherently prone to shift to belief in Christian theology.

In fact, the religion of the northeastern Native Americans was quite hesitant to outright adopt belief in the Christian God until the Eighteenth Century. Paper notes a comment by historian Alfred Bailey suggesting that belief in a “higher force” was not reported amongst the Algonkians by any account of Seventeenth Century explorers or any fieldwork done amongst these Indians (Paper, 4). Paper notes that explicit references to the Algonkian high god “kitchemanito” did not start until the eighteenth century (Paper, 6).

What and/or who is “Kitchemanito,” at least after his full evolution into a high god? The concept can perhaps be explained best by a modern elder of the Ojibwa Tribe of central and eastern Canada, who calls him “Kitchi-Manitou” or “The Great Mystery.” The elder writes that “the creation story of the Ojibwa begins with nothing because in the beginning there was nothing. There was nothing but an all-consuming dark void. Nothing that is … except … possibility. What I mean is this: Although there was nothing, it was conceivable that there might be something other than nothingness. And if it was conceivable that there was a single something other than an all-consuming dark void, then maybe many other things were possible, too. The greatest possibility was that everything that we know and everything that we don’t know could exist. It could all be. A human mind is not capable of envisioning and creating that much possibility. It takes a being with unfathomable powers to envision the possibility of everything and then to bring it all into existence. Some people call the being God. Some people call the being Allah. The Ojibwa call this being Kitchi-Manitou—the Great Mystery” (Native Art in Canada).

Image: Modern Depiction of the Kitchi-Manitou.

Such a high god concept was not cemented until the 1700s. Yet the story of northeastern Native Americans adoption of Christian religious concepts and attitudes toward nature is too complex and diverse to be delineated by the presence or inexistence of explicit and consistent Indian professions of a high god’s existence. Consider, for instance, the 1666 or 1667 account of a man named Allouez. “The Savages [of the Outaouacs] recognize no sovereign master of Heaven and Earth…,” he records, “[but] the Iliniouek, the Outagami, and other Savages towards the South, hold that there is a great and excellent genius, master of all the rest, who made Heaven and Earth; and who dwells they say, in the East, toward the country of the French” (Paper, 4-5).

Paper also shows evidence of conversions void of any disillusionment with traditional Native American religious practices. He points to the narrative of Jesuit Father Andre, who noted, “When I arrived among them at the end of 1673….they [the Menomini of present day Wisconsin] believed that the sun was the master of life and of fishing, the dispenser of all things….After disabusing them of the idea which they had of the sun, and explaining to them in a few words the principles of our faith, I asked them whether they would consent to my removing the picture of the sun, and replacing it by the image of Jesus crucified. They replied, all together and repeatedly, that they consented; and that they believed God was the master of all things…[following the appearance of sturgeon the next morning,] all said to me: ‘Now we see very well that the spirit who has made all is the one who feeds us….” (Paper, 5).

The instability of Indian conceptions of a high or supreme god are displayed in a 1671 account of a Dablon who lived amongst the Illinois. “[They] worshipped only the Sun. But, when they are instructed in the truths of our Religion, they will speedily change this worship and render it to the Creator of the Sun, as some have already begun to do” (Paper, 5). Irregardless of explicit and/or unwavering belief in a high god of the Christian flavor, it is clear that many northeastern Native Americans’ spirituality and worldview was shifting toward the European. For this reason, we can’t presume that lack of widespread evidence in the Seventeenth Century of conversion to specific and consistent belief in a supreme being denotes no popular Native American adoption of more European-like attitudes toward nature.

Attitudes were shifting, and not only because of what the Europeans brought to the table. Elements of Native American religion may have actually prompted adoption of the white man’s ways and religion. As Alfred Goldsworthy Bailey’s holds in his essay on The Conflict of European and Eastern Algonkian Cultures, 1505-1700, “conversion was promoted by the fact that the success of a group was attributed by the group to its gods”; the success of the Europeans was taken as evidence that “their gods must have been more potent than [the Indians’]” (Bailey, 128). This is to say that some Native Americans may have been converted to European ways through reverence and respect for their power and what such power indicated about a people in the traditional Native American belief system. Europeans and their ways must have been superior or somehow blessed by the merits of their favor with gods to account for their fortune. Thus, many Native Americans of New France embraced European ways and participated in what commerce that they could—that is, the fur trade.

Certainly, disease and materialistic motivations alone cannot explain shifting values amongst the northeastern Native Americans toward more European attitudes regarding nature; elements of traditional belief systems themselves could have conceivably contributed to such a transition.

What proportion of Native American’ changed in their attitudes toward nature, specifically in their spiritual relationships with animals? Ultimately enough to hunt many mammalian species across northeastern North America into endangerment!

European material culture, the pressure to match European power, disillusionment with nature and traditional practices in a time of pandemic, and attraction to the Christian and European spiritual and social order were all likely playing a significant role in the conversion of such individuals, considering how the influence of any one of these factors complements that of the others. By and large, the course of Seventeenth Century history evidences that there did not exist enough people or simply people with enough power to resist the forces within northeastern Native American societies that were rejecting traditional culture and participating in unsustainable European-style exploitation of a continent’s animal resources.

Father Chrestien Le Clercq’s 1691 account in his book documenting his twelve years amongst the Gaspesian Indian of eastern Canada presents evidence that the transition toward typical Christian and European views of the time toward nature was not yet complete in northeastern Native American societies (at least as far a typical devout Christian would be concerned). However, the sun was now being consulted for permission to hunt mammalian game instead of the animals directly.

Again, this account takes place roughly a quarter century after the devastating ecological consequences of the fur trade had already climaxed: “[The Gaspesians] performed no other ceremony than that of turning the face towards the sun,” Le Clercq writes. “They commenced straightway their worship by the ordinary greeting of the Gaspesians, which consists in saying three times, Ho, ho, ho, after which, while making profound obeisances with sundry movements of the hands above the head, they asked that it would grant their needs: that it would guard their wives and their children: that it would give them the power to vanquish and overcome their enemies: that it would grant them a hunt rich in moose, beavers, martens, and otters, with a great catch of all kinds of fishes: finally they asked the preservation of their lives for a great number of years, and a long line of posterity” (Le Clercq, 157).

All in all, evidence suggests that the Seventeenth Century transition in northeastern Native Americans relationship with nature would not have occurred in the absence of contact with Europeans and what they brought with them. It is also clear that the Seventeenth Century collapse in furbearer populations in Canadian ecosystems preceded the complete collapse or transition of these traditional Native American value systems (if they have ever completely collapsed).

Lastly, it is clear that it only took a handful of people and entities back then willing to exploit nature unsustainably to potentially ruin a system critical for society at large. The Native Americans of New France failed to reign in individual Indians when their activities threatened the ecosystems upon which their societies relied. Likely they had many reasons to justify such inaction, like we have for not acting strongly enough to halt the global sustainability crisis. Such reasons usually involve keeping up in a high-pressure rat race for wealth, power, and survival.

But at the end of the day, a species that destroys its own ecosystem is as responsible for its fall as any external driver. We are all to blame for systemic collapse if we cannot collectively stand up and stop the forces directly responsible for it.

Unfortunately, humanity is now doing essentially the same thing that the Native Americans involved in the fur trade did to their societies, only on a planetary scale! Of course, this time there is surely no pressure encouraging us from the outside to destroy the planetary system upon which we rely?

For a God who tells us to live only for the hereafter is a misinterpretation of the biblical one; humanity is to tend prudently to the garden of the Earth and, at least according to the Jesus of the Christian gospels, bear fruit to enjoy the fruits of God’s kingdom. It thus seems unreasonable (at the very least painfully ironic) for us to take promises of eternal life for granted when our ways have potentially rendered the life of the world we were entrusted by God to sustain unnecessarily short.

Before the last vestiges of fruit on the tree of life in our age burn, we should recognize that, if we fail so miserably in our basic responsibilities as a species and, for the faithful, as stewards of creation, we will likely get very, very badly burned.

References:

- An Account of the Canadian Mission: The Society of Jesus Introduced Into Canada, or New France (1610). The Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents: Travels and Explorations of the Jesuit Missionaries in New France: 1610-1791, Edited by Reuben Gold Thwaites, The Burrows Brothers Company, Publishers, 1896 (p. 205). https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Jesuit_Relations_and_Allied_Document/E1hNAQAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=he+Jesuit+Relations+and+Allied+Documents:+Travels+and+Explo-+rations+of+the+Jesuit+Missionaries+in+New+France,&printsec=frontcover

- Attfield, Robin (1983). Christian Attitudes to Nature. Journal of the History of Ideas. Vol. 44 (3) (pp. 369-386). https://www.jstor.org/stable/2709172?searchText=au%3A%22Robin+Attfield%22&searchUri=%2Faction%2FdoBasicSearch%3FQuery%3Dau%253A%2522Robin%2520Attfield%2522&ab_segments=0%2Fbasic_phrase_search%2Fcontrol&refreqid=fastly-default%3Ac9488df8b3abb2913f08b0697fb85fb7

- Bailey, Alfred Goldsworthy. The Conflict of European and Eastern Algonkian Cultures, 1505-1700, 2nd Edition. University of Toronto Press (pp. 128). https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/10.3138/j.ctt15jjfq3.15.pdf?refreqid=fastly-default%3A4ac3dbe76bf63bd2ed5e458c55a22e00&ab_segments=&origin=&initiator=&acceptTC=1

- Biard, Father Pierre (1611). First Mission of the Jesuits in Canada: Letter from Father Pierre Biard, to the Very Reverend Father Claude Aquaviva, General of the Society of Jesus, Rome. The Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents: Travels and Explorations of the Jesuit Missionaries in New France: 1610-1791, Edited by Reuben Gold Thwaites, The Burrows Brothers Company, Publishers, 1896 (pp. 127-137).https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Jesuit_Relations_and_Allied_Document/E1hNAQAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=he+Jesuit+Relations+and+Allied+Documents:+Travels+and+Explo-+rations+of+the+Jesuit+Missionaries+in+New+France,&printsec=frontcover

- Indian Notes and Monographs: A Series of Publications Relating to the American Aborigines. Guide to the Museum. First Floor (1922). Edited by F. W. Hodge, The Library of the University of California Riverside (pp. 23-24 and 35). https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.31210007385592&seq=32

- Kolbert, Elizabeth (2014). The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History. Henry Holt and Company, New York, New York (pp. 154-59).

- Le Clercq, Father Chrestein (1915). New Relation of Gaspesia With the Customs and Religion of the Gaspesian Indians, Edited by William F. Ganong, The Chaplain Society, 1910 (pp. 157). https://search-alexanderstreet-com.ezproxy.lib.ou.edu/view/work/bibliographic_entity%7Cbibliographic_details%7C4577228#page/1/mode/1/chapter/bibliographic_entity%7Cdocument%7C4577230

- Martin, Calvin. Keepers of the Game: Indian-Animal Relationships and the Fur Trade (1978). Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London, University of California Press (pp. 1-65). https://www-fulcrum-org.ezproxy.lib.ou.edu/concern/monographs/pv63g030k

- Morrison, Kenneth M (2002). The Solidarity of Kin: Ethnohistory, Religious Studies, and the Algonkian-French Religious Encounter. Albany, NY, State University of New York Press. https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=mgSlto5CGBwC&oi=fnd&pg=PP13&dq=Algonkin+French+contact+primary+sources&ots=s7Rc3BH4eQ&sig=d_hGD3-MDZ_cQ9JDEXHQZcDCd2I#v=onepage&q=Algonkin%20French%20contact%20primary%20sources&f=false

- Native Art in Canada: An Ojibwa Elder’s Art and Stories. “The Ojibwa Creation Story. This is the Creation Story of My Childhood.” https://www.native-art-in-canada.com/creationstory.html (Accessed 9 May 2024).

- Paper, Jordan (1983). The Post-Contact Origin of an American Indian High God: The Suppression of Feminine Spirituality. American Indian Quarterly, Vol 7 (4) (pp. 1-24). https://www-jstor-org.ezproxy.lib.ou.edu/stable/1184237

- Poutrincourt, Sieur De (1610). The Conversion of the Savages Who Were Baptized in New France during this year, 1610. The Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents: Travels and Explorations of the Jesuit Missionaries in New France: 1610-1791, Edited by Reuben Gold Thwaites, 1896 (pp. 53-106). https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Jesuit_Relations_and_Allied_Document/E1hNAQAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=he+Jesuit+Relations+and+Allied+Documents:+Travels+and+Explo-+rations+of+the+Jesuit+Missionaries+in+New+France,&printsec=frontcover

- Richards, John F. (2003). The Unending Frontier: An Environmental History of the Early Modern World. University of California Press, Ltd. (pp. 472-74).

- Stankey, George H (1984). Beyond the Campfire’s Light: Historical Roots of the Wilderness Concept. Praise of Humility: The Human Nature of Nature, Research Social Scientist, Intermountain Research Station, USDA Forest Service, Missoula, Montana (pp. 9-14). https://winapps.umt.edu/winapps/media2/leopold/pubs/212.pdf

- The Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents: Travels and Explorations of the Jesuit Missionaries in New France: 1610-1791, Vol 1, Edited by Reuben Gold Thwaites, 1896. https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Jesuit_Relations_and_Allied_Document/E1hNAQAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=he+Jesuit+Relations+and+Allied+Documents:+Travels+and+Explo-+rations+of+the+Jesuit+Missionaries+in+New+France,&printsec=frontcover

- Williams, Ted (2022). America’s New War on Wolves and Why It Must Be Stopped. Yale Environment 360. Published at the Yale School of Environment. https://e360.yale.edu/features/americas-new-war-on-wolves-and-why-it-must-be-stopped. (Accessed 9 May 2024).