Post 1: Mountain Lions in the Review Mirror

Evil Antlers

In a rare match between a mountain lion and a green anaconda, the big cat will typically attack at the snake’s tail, giving the serpent leeway to wrap and swallow only after it has left fatal wounds. In the hills outside LA, mountain lions face another serpent—this one made of concrete, many lanes wide, and known for swallowing thousands of cars daily.

In the rare event that a mountain lion musters up the courage to cross paths with a California interstate, there is often death and destruction ahead. For instance, Uno, the famed one-eyed mountain lion that roamed Orange County, met her end after being involved in a collision with a vehicle.

Unfortunately, hers doesn’t seem to be a rare misfortune of not being able to look both ways. A 2015 study on the survival and mortality of mountain lions in fragmented, urbanizing landscapes monitored the movements of 74 mountain lions in the Santa Ana Mountain from 2001 to 2013 and found that a total of 34 (or 46%) of the cats died after being struck by a vehicle (Vickers et. al. 2015). A far lower percentage of human deaths are caused by mountain lions, at least directly. In truth, mountain lions may be responsible for saving us from a far greater threat on the roads.

6.5% of all vehicle collisions involve prey that healthier mountain lion populations could keep off the road. Deer–yes, deer!–are the deadliest animal in North America in terms of human causalities resulting from encounters, not some fearsome predator. The numbers are staggering. Calum Cunningham, Laura Prugh, and their colleagues at the University of Washington compiled U.S. data and found that some 2.1 million deer-related collisions occur in the country each year, amounting to some $10 billion in losses, 59,000 human injuries, and 404 human deaths (Cunningham et. al. 2022). We can even estimate the costs of mountain lion decline to society in terms of deer impacts!

Wildlife ecologist Sophie Gilbert and her team at the University of Idaho compared ecosystem services provided by mountain lions before and after their reintroduction to the Black Hills. They found that the cats reduced deer-vehicle collisions by 9% and saved drivers some $1.1 million (Elbroch 2020). Gilbert’s team also calculated the total services provided if mountain lions were to reestablish in the highly fragmented habitats of the eastern United States, estimating that there would be 155 fewer fatalities and 21400 fewer injuries from vehicle collisions as well as $2.13 billion dollars in saved damages (Elbroch 2020).

Deer populations have exploded in many fragmented and/or urbanizing landscapes across America (with the creatures readily volunteering to mow lawns and strip flowerbeds or standing angelically with horn-like antlers in our headlights).

Even in the face of such bedevilment, however, most Americans would surely rather deal with the deer explosion than the sounds of shotguns going off nearby their children? Much less would they want to invite some not-so-friendly mountain lion into their neighborhood to down the deer. Indeed, mountain lion attacks, though rare, have clawed their way into the news as recently as this summer, when a mountain lion approached a group of six picnickers in a Los Angeles County park and and ended up attacking a five-year-old boy.

Nevertheless, big predators prowling the periphery of urbanized areas would help with deer population management. What is more, predators are essential in the fight for a sustainable world. That’s because predators protect our plants from the possibility of herbivore populations getting out-of-control. Essentially, a mountain lion whose tracks have vanished from our woods and canyons has left a huge carbon footprint in his or her place.

Big Cats Rule

The mountain lion once had a range that stretched over the whole of the Americas. The species still puts a paw down in Patagonia and breathes the biting air of the Yukon.

Figure 1: Current versus historic range of the mountain lion.

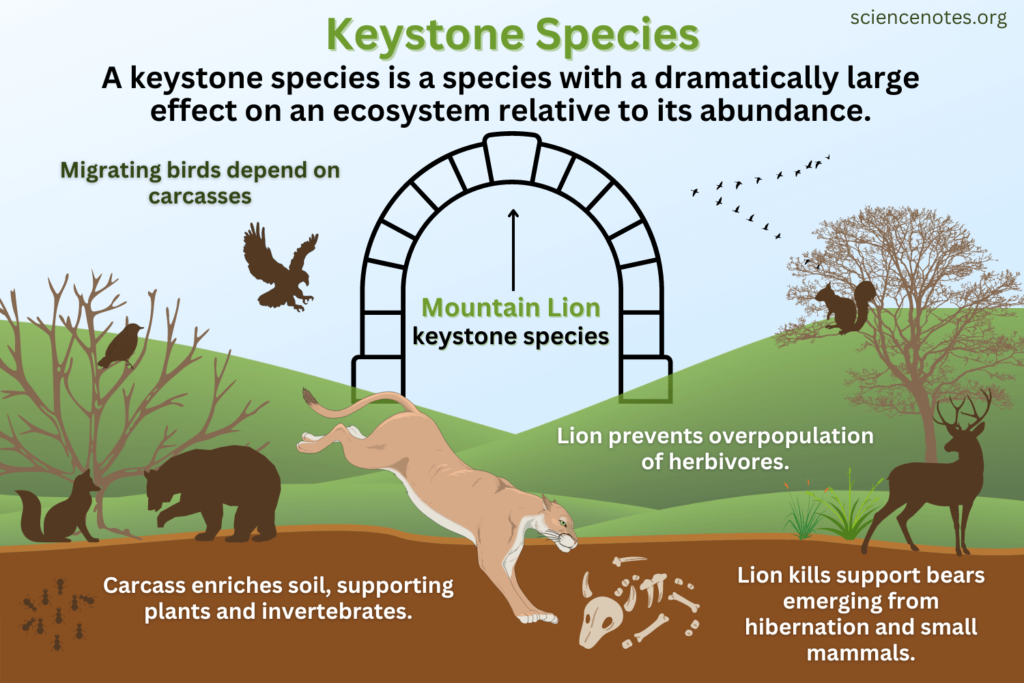

As an apex predator, the mountain lion serves as what biologists term a keystone species. With one in place, an ecosystem remains stabilized something like an archway; the top dog checks herbivore populations that would otherwise threaten the system’s green foundations (Figure 2). Without a keystone species in place, on the other hand, whole ecosystems become susceptible to collapse.

Figure 2: Trophic effects of the mountain lion, a keystone species across the Americas (Helmenstine, 2023).

Someday in the not-too-distant future, we may see a world where mountain lions do not walk and new generations of trees simply do not make it. In this world, the archways of a once great city will hold no keystone (at least not one carved with the face of a ruling cat or very effective at doing its job). The land beyond the city gates will present countless saplings nibbled to death by ungulates. As these aborted generations eventually begin waving goodbye to their rotting parents, carbon dioxide will spew into the atmosphere and conceivably drive the Holocene, as we call the uniquely stable and favorable climatic epoch in which civilization was able to take root and grow with reliable agriculture, to an abrupt end.

Lanes That Seldom Cross

The reasons for mountain lions’ decline are fairly straightforward.

Relative to other mammalian species, mountain lions require a lot of habitat to survive—a huge highway lane for life, if you will!

This fact seems counterintuitive when we consider the species’ diet preferences. They go for deer before anything else—animals often concentrated in small areas. Mountain lions will also eat small animals and even insects, which are in no small supply in most areas. Yet mountain lions are also highly territorial animals. In the event two or more of them try to claim the same ground, fighting and death can result. Thus, mountain lions have low population densities despite their flexible diet and high-density prey.

Although they can breed year-round, with low population densities, mountain lions encounter potential mates less frequently than many other large mammalian species. They roam over large areas to find a mate, seldom crossing. This means that if mountain lion populations take a hit, their numbers may not be able to recover as quickly as other species’.

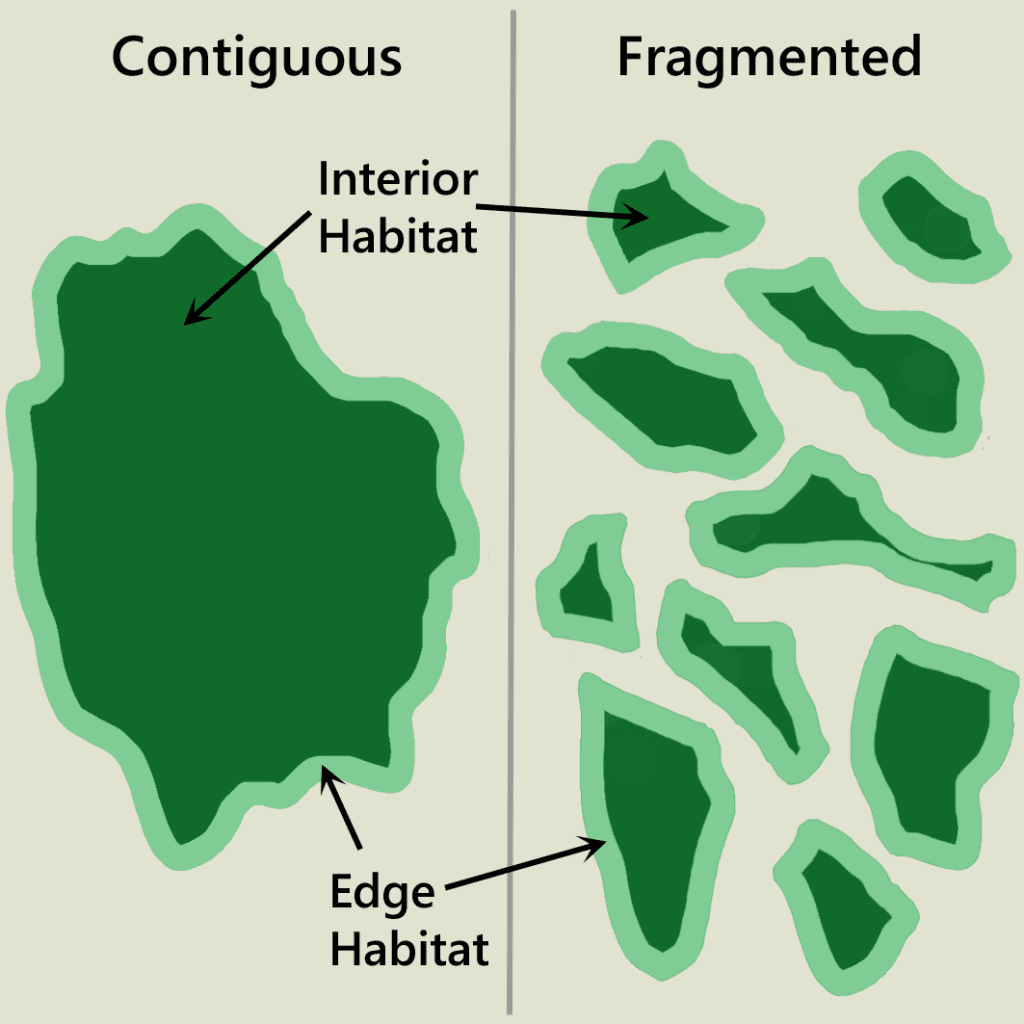

With the staking of uncontested territory at the forefront of a mountain lion’s mind, it’s somewhat surprising that they are prone to turn from highways before they muster the will to cross them. But the cats do shy away from man’s transformations of the land. Thus, mountain lions’ decline comes down to one big extinction driver: habitat loss. Specifically, it’s a matter of habitat fragmentation, or the division of a larger habitat into smaller, unconnected areas.

Mountain lions’ decline seems a story of our “once great city” destroyed (rather than primed for sustainable growth) by roads.

Figure 3: Habitat fragmentation entails the division of a single, large area of habitat into multiple smaller and disconnected areas with reduced interior or core area.

Drifting Off the Highway of Life

If a presidential poll of the 2024 contest between Donald Trump and Kamala Harris was conducted with a small sample size, chances are pretty high that it wouldn’t reflect the opinions of the American people. But with a large enough, random sample, pollsters know that random deviations from the opinions held by the population at large balance out and polling data converges upon the true population parameter for the voting public.

A similar effect is often seen when a wild population becomes small. Locally, chance events, such as the random passing of one allele (biologists’ word for a version of a gene) on to the next generation over other alleles, can sway the distribution of alleles seen in a local isolated metapopulation. On the other hand, in a larger, integrated population of organisms, unlikely genetic events will even out and reflect the existing gene pool of the population.

Biologists call chance-driven evolution in small populations genetic drift. Often drift can eliminate alleles from a population all together, diminishing the genetic variability that empowers populations to adapt in the face of change via natural selection. Think of it as the genetic variability as what empowers organisms to change lanes on the highway of life when one or more lanes get backed up with insufferable traffic. Without genetic variability, the ability of populations to adapt to change essentially shuts down.

Today, populations are increasingly fragmented and vulnerable to genetic drift and declining genetic variability at the same time that the environment is rapidly changing. Many species have little or no ammunition that will give them a new shot at life in such a world. Among these species is the beautiful mountain lion.

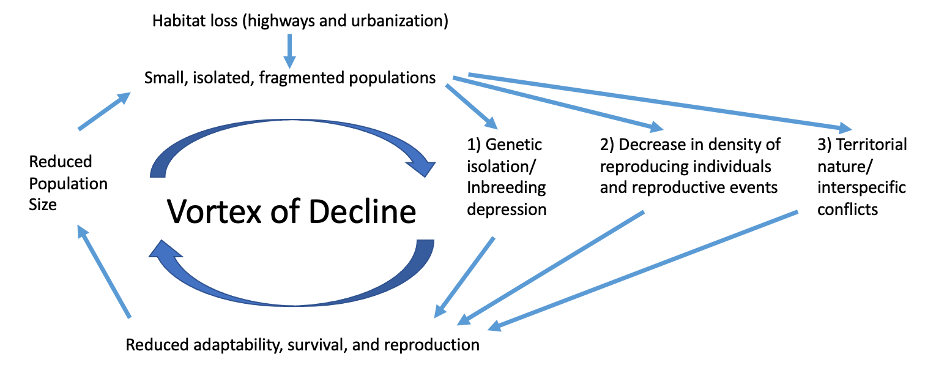

Figure 4: The vortex of decline for mountain lions. The species is particularly vulnerable to extinction in areas of encroaching habitat fragmentation and urbanization on account of genetic drift, inbreeding, decreases in the density of reproductive events, and interspecific conflicts (fights with other mountain lions). These factors reduce individual adaptability, survival, and reproduction and drive a vicious cycle.

Figure 4 shows the vicious vortex of decline and/or extinction for mountain lions. Roads and urbanization fragment the cats’ habitat, which, because of their wariness to cross through such development, in turn fragments populations of the animals. Drift, decreases in the density of reproductive events, conflicts over territory, as well as inbreeding (which can unmask deadly recessive traits) reduce these populations further, with inbreeding and drift intensifying as population size decreases and driving the vortex even faster.

Figure 5: Current IUCN Red List Status of the mountain lion. Least Concern indicates that the IUCN has evaluated the species but that it is neither threatened, near threatened, or conservation dependent on account of its populations still being plentiful in the wild (Nielson et. al., 2016).

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (or IUCN) status of the mountain lion is Least Concern with a population that is decreasing, owing to the fact that the mountain lion is well established and stable across most of its range (Nielson et. al., 2016). As such, the IUCN does not consider mountain lions a conservation concern. However, this status is misleading. Mountain lions ARE experiencing rapid declines with high local extinction risk in regions where their habitat has been ripped apart like a carcass by urbanization and roadway development.

In 2019, biologists from around the U.S. and National Park Service officials conducted a viability analysis of mountain lion populations in the Santa Ana Mountains. Their models predicted that, at current low or nonexistent levels of immigration, there is a 16-21% change that demographic processes alone drive mountain lions to extinction in the area within the next 50 years (Benson et. al., 2019). Moreover, the study suggested that there is real concern of an inbreeding depression in the Santa Anas. Irregardless of demographic factors, such an event would erode genetic diversity to a point where extinction becomes highly probable (Benson et. al., 2019).

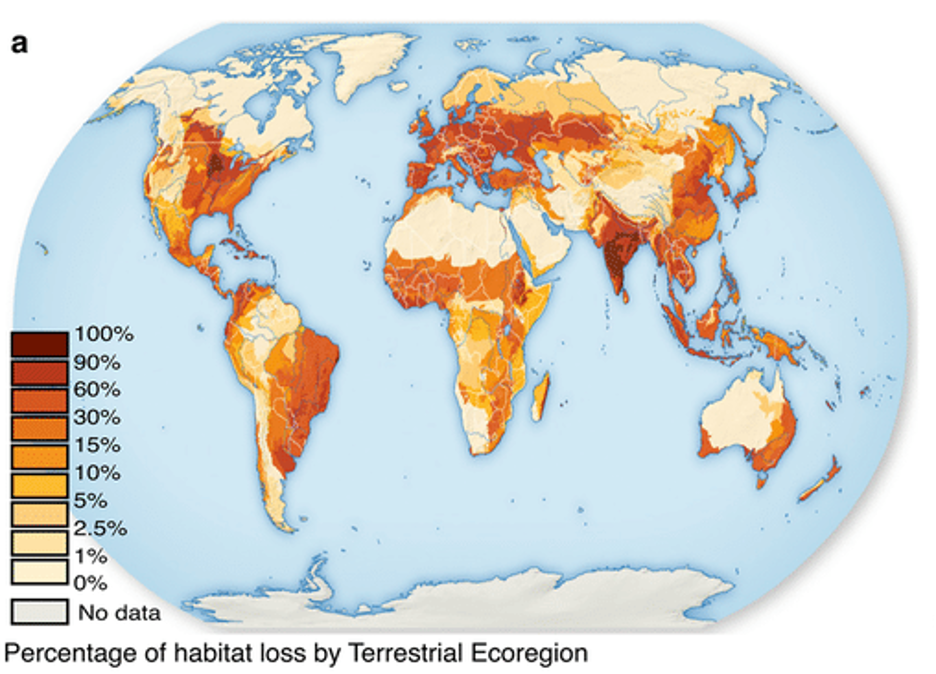

Comparing Figure 1 to Figure 6 (which shows a map of the extent of habitat loss across the globe), we observe how the mountain lion has either been driven out or is spiraling toward extinction in areas of the U.S. characterized by greater than 30% habitat loss. The hot spot of extinction risk where the species still exists is California (Figure 1, 6).

Figure 6: Map of the percental of wild or natural habitat lost across the terrestrial ecoregions of the Earth.

Considering that mountain lion populations have less probable and frequent reproduction events and cannot easily recover from declines, the seriousness of the situation with mountain lions in areas of significant habitat fragmentation comes into clear focus.

In the end, the lanes in which humans and mountain lions live do not seem to cross well. Or do they?

Double Decker Highways

There’s really only two viable solutions for mountain lion conservation. The first is to provide the cats a way around humanity in the form of wildlife crossings and corridors.

Figure 7: A rendering of the planned wildlife bridge over 10-lane highway 101 in the Santa Monica Mountains.

Wildlife crossings entail overpasses paved with grasses, rocks, and bushes. They provide linkage between habitats that, as far as an animal scared to cross a highway is concerned, might otherwise exist on opposite sides of the Earth. In landscapes shattered and scarred by urban and road development, these bridges may one day hold the face of the wild together like monumental Band-Aids. The crossing depicted in Figure 7 has a price tag of $90 million, 60% of which was provided by private donors. The rest came from funds set aside by the State of California for conservation purposes. The crossing should pay for itself in saved wildlife-vehicle collision damages within a couple of decades. It should allow mountain lions to maintain the ranges they need to keep from getting sucked up in the vortex of decline.

But the creation of these viable habitat linkages does not happen overnight. Their construction must be coordinated to provide the large-scale habitat connectivity species like the mountain lion require. This means that these linkages often need to be planned at national and/or state levels (an unfortunate practical reality that often pits potential linkage projects against a long political tradition of local land management in the West and all that Washington drama we know about). Linkages also require significant monitoring of animal movements to inform their design, ensuring that investment in such projects will not only create jobs for many highway workers but also for scientists studying those highways of life.

The second action we must take as a society to keep mountain lions around is to prevent fragmentation of their habitat in the first place. This means valuing our national and state parks as well as other often less appreciated protected areas.

A Road Back To The Garden

If we want to keep the cats around, wildlife crossings and linkage networks are clearly essential over major interstate highways in the face of widespread fragmentation of mountain lion habitat. Such actions will also protect the vast American ecosystem and the services it provides. These include the inherent value of American forests. They also include the critical job healthy forests do for us capturing atmospheric carbon dioxide and thus mitigating climate change and the risk of global systemic collapse. Finally, protecting mountain lions will help society deal with the pestilential and too often deadly fallout of rampant deer population explosions.

With a big cat roaming not too far off, we can better enjoy our newly planted pansies for more than a day or two. We can also rest more assured that our gardens and our place in the “Garden of Eden”–which for mankind has essentially been represented by the wonderful but fragile climatic epoch of the Holocene–isn’t getting consigned to biblical history anytime soon.

One small step toward a future full of life and pleasantries lies in building natural gardens over our highways. We get together and accomplish this and perhaps the death of big cats won’t deliver us into the clutches of a garden nuisance much more fearsome than any deer—that is, the specter of the sudden end of the stable Holocene.

References:

- Benson, John F.; Mohoney, Peter J.; Vickers, T. Winston; Sikich, Jeff A.; Beier, Paul; Riley, Seth P. D.; Ernest, Holly B.; Boyce, Walter M. 2019. Extinction vortex dynamics of top predators isolated by urbanization. Ecological Applications, Ecological Society of America. https://esajournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/eap.1868

- Benson, John F.; Sikich, Jeff A; Riley, Seth P. D. 2020. Survival and competing mortality risks of mountain lions in major metropolitan area. Biological Conservation, Vol 241. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0006320719311346

- Collinge, Mark. 2008. Relative Risks of Predation on Livestock Posed by Individual Wolves, Black Bears, Mountain Lions, and Coyotes in Idaho. Proc. 23rd Vertebr. Pest Conf. (R. M. Timm and M. B. Madon, Eds.) Published at Univ. of Calif., Davis. 129-133.

- Cunningham, Calum X.; Nunez, Tristen A.; Hentati, Yasmine; Reese, Ellie; Miles, Jeff; Prugh, Laura R. 2022. Current Biology. Permanent daylight savings time would reduce deer-vehicle collisions. Current Biology, Vol 32, Issue 22. https://www.cell.com/current-biology/fulltext/S0960-9822(22)01615-3?_returnURL=https%3A%2F%2Flinkinghub.elsevier.com%2Fretrieve%2Fpii%2FS0960982222016153%3Fshowall%3Dtrue

- Elbroch, Mark. 2020. The Cougar Conundrum: Sharing the World with a Successful Predator. Washington, Covelo, Island Press. https://islandpress.org/books/cougar-conundrum#desc

- Gammon, Katharine. 2022. Animal crossing: world’s biggest wildlife bridge comes to California highway. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2022/apr/09/wildlife-bridge-california-highway-mountain-lions. Accessed on 19 April 2024.

- Golfarb, Ben. 2020. When wildlife safety turns into fierce political debate. High Country News. https://www.hcn.org/issues/52-1/wildlife-when-wildlife-safety-turns-into-fierce-political-debate/. Accessed on 19 April 2024.

- Hogue, Aaron S.; Breon, Kathryn. 2022. The Greatest Threats to Species. Conservation Science and Practice, Vol 4, Issue 5. https://conbio.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/csp2.12670

- National Wildlife Foundation. “Mountain Lion.” https://www.nwf.org/Educational-Resources/Wildlife-Guide/Mammals/Mountain-Lion. Accessed on 19 April 2024.

- The Nature Conservancy. Destination Nature: A Path for Mountain Lions. https://www.nature.org/en-us/what-we-do/our-priorities/protect-water-and-land/land-and-water-stories/a-path-for-mountain-lions/. Accessed on 19 April 2024.

- Nature Trust British Columbia. 2022. https://www.naturetrust.bc.ca/news/habitat-fragmentation-and-how-land-conservation-is-putting-the-pieces-back-together. Accessed on 19 April 2024.

- Nielsen, C.; Thompson, D.; Kelly, M.; and Lopez-Gonzalez. 2016. Puma concolor. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2015: e.T18868A97216466. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-4.RLTS.T18868A50663436.en. Accessed on 19 April 2024.

- Nijhuis, Michelle. 2021. Beloved Beasts. New York, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc, p 250.

- Rocamora, Blai Vidiella; Sardanyes, Josep; Fontich, Ernest; and Valverde, Sergi. 2021. Habitat loss causes long extinction transcients in small trophic chains. Theoretical Ecology, Vol 14, Issue 12. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/352666007_Habitat_loss_causes_long_extinction_transients_in_small_trophic_chains

- Helmenstine, Anne. 2023. Science Notes. “Keystone Species – Definition, Examples, Importance. https://sciencenotes.org/keystone-species-definition-examples-importance/. Accessed on 19 April 2024.

- Vickers, Winston T.; Sanchez, Jessica N.; Johnson, Christine K.; Morrison, Scott A.; Botta, Randy; Smith, Trish; Cohen, Brian S.; Huber, Patrick R.; Ernest, Holly B.; Boyce, Walter M. 2015. Survival and Mortality of Pumas (Puma concolor) in a Fragmented, Urbanizing Landscape. Plos One, Vol 10, Issue 7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4503643/