Big, Bad, and Starved

Before mankind, being the biggest and the strongest had always been the name of the game between predator and prey. Brawn had been the way to win the evolutionary arms race.

66 million years ago, one of these epic battles had been climbing toward an ever-growing climax. Increasingly large dinosaurs roamed the Earth and vied for dominance. An asteroid the size of Mount Everest brought an abrupt end to all that, with only the small ground animals continuing on.

Mammals in particular would star in the next act for the Earth. They’d bulk like bodybuilders all the way until the sixth, human-lead mass extinction began hurtling things called weapons and using these crazy things we call big brains. The advantage of physical size and strength had suddenly become a liability for many species as skinny little bipedals began taking down what offered the most meat at unsustainable rates (Figure 9). Wherever mankind has migrated and multiplied, it has been the consistent case for forty thousand years that megafauna have eventually dwindled, departed, and/or died.

Figure 9: Depiction of what’s become of Pleistocene mega-fauna after humanity got hands on them. “RIP Woolly Mammoth and Sabre-tooth Tiger”

As megafauna burned over bonfires, forest grew thick as lion manes and sprung across the land like they had come into mobile animal form. Pretty soon, the fire danger was maxed out. The world burned. Savannas swept over the continent of Africa and a big cat, among the last of the megafauna, found a steady niche he could be proud of.

He was “the king of the jungle,” the charming star of a Disney classic, and he’ll always be a symbol of the victorious Christ. But the African lion is now in serious danger of extinction in the wild and may well have to place his hopes in a rather miraculous resurrection from the dead.

The bigger an animal, the more likely it is to suffer in the face of stresses from loss of habitat or other factors, simply because it requires more resources.

Lions live in highly territorial prides in regions of grassland, savanna, dense scrub, and open woodland that may range from 20 square kilometers when prey is dense to 400 when it is hard to find. They require some 5-7 kilograms of meat a day with their prey preference being large, hoofed animals such as wildebeests, zebra, and antelope. Prides are thought to maximize the efficiency of energy use by enabling more effective group hunting, territory defense, and shared meals.

Female lions only mate about once every two years and make considerable time and energy investments in the rearing of cubs. Bearing the downsides to size in battles for fitness and survival like the mammalian megafauna consigned to the pages of natural history before them, lions are thus slower to reproduce and recover from stresses placed upon the population. It suffices to say that, when humans push fiercely competitive and hungry lion prides into smaller and smaller areas, there is risk that they may go the way of the mammoth, struggling to hold ground and resources against other prides and breeding at unsustainable rates for recovery. Pushed to feed on nearby livestock, they could also end up going the way of America’s 20th century big bad wolves!

All told, the African lion may be among the next megafauna on humanity’s hitlist.

A Kicking Beast with Ears of Corn

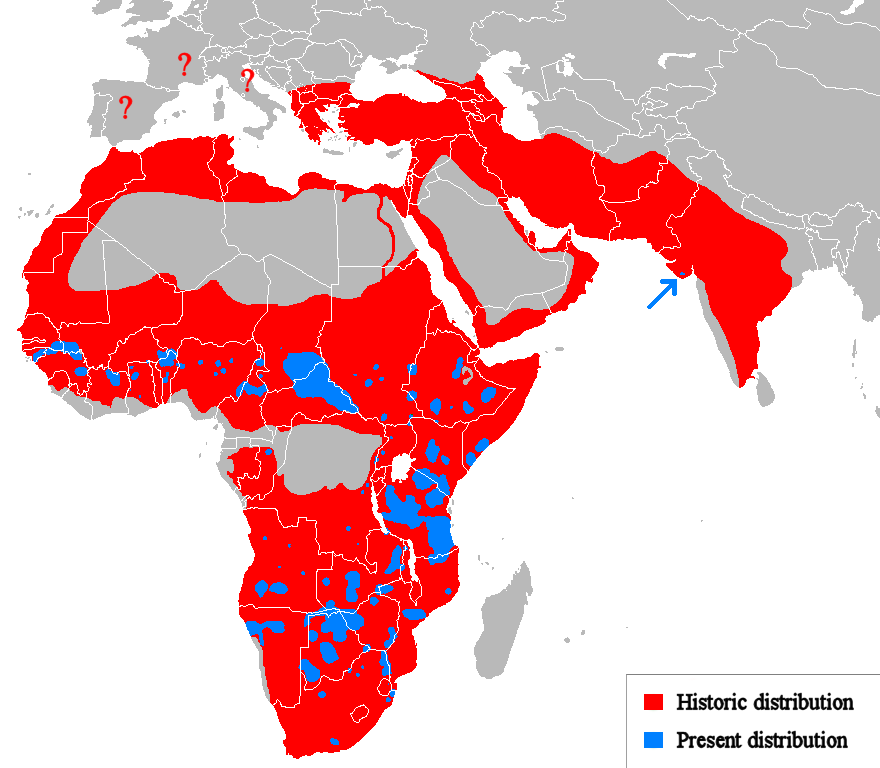

The aspect of the conservation situation with African lions that is particularly worrisome is that much of the remaining habitat for the animals is quite suitable for agriculture and pastoralism (this is in contrast to the situation with mountain lions and wolves in North America, who occupy valued boreal sanctuaries). It is generally understood by biologists that agriculturalism, pastoralism, and retaliation for depredation pushed lions out of a habitat that once encompassed much of the surface of the Earth, stretching their slinking cat walk across Europe, the whole of Asia and North America, and down as far as Peru (though, as seen in Figure 10, in concentrated numbers the historical range is only considered to have reached as far from the continent of Africa as India and southeastern Europe) (Patterson, 2004).

What’s to stop the measly portion of his former glory that the lion still enjoy from being taken from him as well?

Figure 10: Historical versus Present Range of the African Lion. Lions have lost 80% of their historical range (African Parks).

Bruce Patterson and others with the Tsavo Research Center and Field Museum in Chicago (where two devilish maneaters that once killed dozens are now kept with their stomachs forever stuffed) studied the preferences of lions for traditional prey versus livestock around Kenya’s largest park system. The area is now-quite-densely-populated. Patterson and his colleagues found that depredations upon livestock represented around 5.8% of the diet of ranch lions (Patterson, 2004). This 5.8% amounted to a $290 cost to ranchers for each depredating lion per year, a number that goes a long way in an African economy and is certainly enough to provoke a strong human reaction (Patterson, 2004). Moreover, cows are a large ungulate like lions preferred savanna prey species, and it’s not hard to see how appealing they could be to lions met with the hardship of losing their natural habitat and a fight with a pride vying over what’s left.

Lions have likely been in conflict with pastoralists for centuries, and now as a species they are at real risk of sudden death. The IUCN classifies the African lion as “Vulnerable” with a population of only 23,000 that are decreasing (Nicholson et. al., 2023). The lion population halved from 1993 to 2014, and at current rates the species may well be extinct in the wild by 2050 (African Parks).

Figure 11: Current IUCN Red List Status of the African lion (Nicholson et. al., 2023).

A 2015 study by David Brugière, Bertrand Chardonnet, and Paul Scholte found that low prey density, persecution by people inside and near the borders Africa’s protected areas, and diseases were the major factors in local lion extinction events (Brugière et. al., 2015). They noticed that protected areas with lion populations were larger than those where the species had gone extinct and reasoned that edge effects could be behind this (Brugière et. al., 2015). Human population density around protected areas did not correlate with lion extinction, so Brugière and his colleagues suggested that mobile pastoralists were the culprit behind these edge effects (Brugière et. al., 2015). In a word, the evidence points toward persecution of park lions by active exterminators who have had their livestock preyed upon. Africa’s parks are clearly not as protected as North America’s.

If the status quo in Africa doesn’t change, a day is coming when there is simply not going to be any place for lions to find refuge from an extinction driver in the form of a beast that kicks like a shotgun.

A Star We Can’t Let Burn Out

It would be terrible to many of us to lose the real-life Simba and one of the most beautiful symbols of Jesus.

Figure 12: A being crowned with Tsavo thorns. Some say he’s threatened with extinction in our times.

It would also be a real bummer to end safari adventures, not merely for global tourists but local African villages and towns. Indeed, wildlife tourism is critical to the economies of such places, so much so that many have built a strong and successful tradition of community conservation efforts. Specifically, locals form cost-sharing arrangements with nearby protected areas to compensate victims of depredation, and well-funded international conservation organizations employ very capable trackers from the towns and villages to thwart poachers (Nijhuis, 2021).

Such soldier-like conservancy rangers should be hired to patrol African parks and stop mobile pastoralist exterminators!

African lions are, like mountain lions and wolves in North America, a keystone species that protects grasslands from fat herbivore populations. The loss of a marvelous ecosystem in the African savannas without its “king” to protect it would be inherently tragic. What is more, grasslands remain significant carbon sinks that we often forget looking to our woods, and their preservation defends the auspicious features of the blue dome that stretches over them wherever they are.

We should work to get more African communities into contact with international organizations that might fund compensation grants to ranchers who have lost livestock to the king of the animals. We should also organize to bring in the money of concerned citizens—ranks of donors that one day may include the likes of you and me—to provide such compensation to pastoralists proactively dealing with their lion problems. Finally, we should fund the construction of park fences around protected areas in Africa to keep the beasts in or out (depending on your perspective).

We’ll have to use the brains that helped us conquer the surface of the Earth better if we want to keep our planet’s big, beloved predators from becoming part of a long tradition of mammalian carnage. In fact, this Predatory Carnivores post series has demonstrated that we just might have to use our brains hard if we want to live in the world we want. Let’s make sure the road of life isn’t a dead-end straightaway. Let’s get off the “meaningless line of indifference,” as Timone the Meerkat called it in the live action version of Disney’s The Lion King, and wake up to our critical role as a friend to other species in a never-ending “Circle of Life”.

If we’re foolish enough to choose not to, we should really remember the teeth of the big cat and the Earth when we grab her by the tail!

References:

- African Parks. Lion Conservation. https://www.africanparks.org/save-lions. Accessed on 19 April 2024.

- Brugiere, David; Chardonnet, Bertrand; and Scholte, Paul. 2015. Large-Scale Extinction of Large Carnivores (Lion Panthera Leo, Cheetah Acinonyx Jubatus and Wild Dog Lycaon Pictus) in Protected Areas of West and Central Africa. Sage Journals. Tropical Conservation Science.https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/194008291500800215’

- Nicholson, S.; Bauer, H.; Strampelli, P.; Sogbohossou, E.; Ikanda, D.; Tumenta, P.F.; Venktraman, M.; Chapron, G; and Loveridge, A. 2023. Panthera leo. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2023: e.T15951A231696234. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2023-1.RLTS.T15951A231696234.en. Accessed on 19 April 2024.

- Nijhuis, Michelle. 2021. Beloved Beasts. New York, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc, p 250.

- Patterson, Bruce D.; Kasiki, Samuel M.; Selempo, Edwin; and Kays, Roland W.L. 2004. Livestock predation by lions (Panthera leo) and other carnivores on ranches neighboring Tsavo National ParkS, Kenya. Biological Conservation, 119 (4), 507-516. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0006320704000163