Buffet Highways

In areas of roadway development, the conservation situation with grey wolves is quite different from that which we saw last post with mountain lions. Mankind has opened a regular buffet restaurant for wolves, but if they get much out of line, it seems man is intent on barbarically killing his own customers!

It’s a story that often starts with a wheeled harvesting machine sawing into the last trees of a Canadian timber cut block. The machine sends splinters of wood flying like some wolf is shaking off the life he’s always known in the boreal forests. This phantom wolf’s coat is dry, but his mouth is wet for prey, which he knows he will find most easily outside the deep woods. Soon ambitious young poplar trees sprout through the fresh cut block. Moose and deer move in, wolves follow, and the ground of the cut runs with ungulate blood thicker than mud.

Recall that mountain lions will evidently avoid roads if they can help it. Moreover that, probably on account of their territorial nature, they do not typically concentrate in areas where prey populations have exploded.

A 2019 study in British Columbia concluded that grey wolves, quite in contrast, are actively using roadway corridors and cut blocks through their natural forest habitat to facilitate more rapid pack movement and take advantage of the maximum prey densities that exist there (Muhly 2019). Wolves selected for regions with higher cut block density over less-modified forest habitat (likely on account of fragmented forest being a high-quality habitat for ungulate prey) and chose areas with higher road densities in regions where road densities were high (Muhly 2019). Wolves were likely to use cut blocks for travel in regions with low road density (Muhly 2019). In a nutshell, Muhly and his colleagues showed that North American grey wolves, unlike mountain lions, prefer and actually thrive with some fragmentation of their traditional boreal habitat.

Highways and cut blocks are indeed serving like fast, all-you-can-eat buffet lines for hungry wolves!

All wolves really require for their habitat needs is sufficient prey and den opportunities. A study by Sarah Sells and her colleagues with the University of Montana’s Montana Cooperative Wildlife Research Unit showed that wolves will carve out territory economically, balancing the benefits of prey availability with the costs of defending their territory from other packs (Sells et. al., 2021). Since larger territories are harder to defend, naturally wolves prefer to stake out smaller areas that support a greater density of prey for the pack (Sells et al., 2021). We see this strategic planning by wolves when we look at territory sizes by ecosystem, notes the International Wolf Center’s Thomas Gable; boreal forest territories, for instance, can be as small as 7.5 square miles, while some territories north of the Arctic Circle (where prey is scarce) can be as extensive as 1000 square miles (Gable, 2021). We likewise see packs executing strategic plans within the same ecosystem, which Sells postulates depends on prey availability, competition from other wolves, and roadway access (Sells et. al., 2021). Sells found that pack territories shrunk with increasing density of low-use roads in the area, likely on account of the wolves being able to travel and find prey more effectively using the roads (Sells et. al. 2021). Larger packs correlated with a smaller territory size, conceivably because they can kill prey more efficiently (Sells et. al., 2021).

It seems that of the major mammalian carnivores I have investigated, grey wolves have weathered the extinction driver of habitat fragmentation the best—even found advantage in it! This is particularly true in areas of forest crossed by roadways. But what about beyond these fast, ungulate buffets, in lands lined with produce and tread by unhurried cattle?

How do wolves fair in regions characterized by more extensive habitat fragmentation?

Big Bad Wolf Hatred

Northern Lower Michigan is not as friendly a landscape for wolves as the state’s upper peninsula. Its coat of boreal and hardwood forests lies shaven, uprooted by agricultural and urban areas, like a canine assaulted by some demented barber. A 2019 study by biologists and foresters evaluated wolf habitat throughout Northern Lower Michigan (Stricker et. al., 2019). They found 1900 square kilometers of high-quality den habitat throughout the region but also inadequate dispersal corridors for wolves (Stricker et. al., 2019). This reality may lead to isolated populations, genetic drift, and inbreeding similar to that which plagues California mountain lions (Stricker et. al., 2019). Additionally, the study warned against the threat of deadly conflict with humans in Northern Lower Michigan as wolves cross into pastoral and urban areas (Stricker et. al., 2019).

Wolves are notably less shy than mountain lions (wolves being the opportunistic animals that approached human trash heaps and eventually found a clean dog collar on their necks). According to the National Agricultural Statistic Service, more depredation upon livestock is indeed a probability when and where wolves pass too deep into human civilization, at least compared with the appetites of other large carnivores.

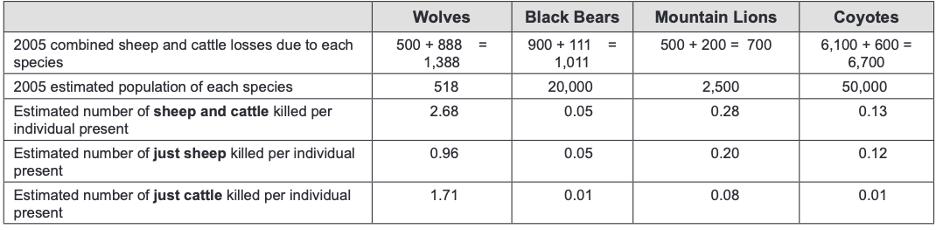

Table 1 from a 2008 study by Mark Collinge summarizes the deaths from different large, mammalian carnivores in Idaho in 2005. Wolves were reintroduced to the state in 1995.

Table 1: Estimated number of livestock killed per individual of each species of large carnivore implicated in depredation in Idaho in 2005 (Collinge, 2008).

Notice in Table 1 that the 1388 livestock deaths attributed to wolves were the second highest (compared to the 6700 attributed to coyotes), but that on a per animal basis wolves were by far the highest (Collinge, 2008). The appetites of the wolves for livestock compared with the desires of mountain lions comes into even clearer focus—in fact, we can almost taste it when we consider that there are only 500 wolves in the state killing some 1388 animals versus Idaho’s 2500 mountain lions killing just 700; it’s undeniable that wolves do have a bad streak in their coats when it comes to messing with livestock (Collinge, 2008).

It is for this reason that, despite their preference for lumbered forest habitat and love of human road development, there has, unfortunately, been a cruel twist to the story of the bold, economical, and opportunistic grey wolf. Significant habitat fragmentation is killing them in a different way than big American cats. Whenever wolves try to ride alongside humans much beyond the forest roads they keep clear of deer, there’s usually somebody riding shotgun—or rather, with a loaded gun ready to keep wolves away from their livelihood!

Mountain lions resist territorial compression into areas where prey populations are dense, such as marginally fragmented forests, and can’t take advantage of what these new transformed landscapes have to offer as wolves have. Yet wolves provoke conflict with humans, moving into agricultural and pastoral lands either because they smell meaty temptations or because prime territory has been claimed by other packs.

The venturesome, opportunistic animals become “big bad wolves.”

However, there’s a part of the old fairy stories starring wolves that you’ve probably never heard–a whole history of irrational grey wolf villainization that culminated in a ravenous campaign of extermination and nearly wiped the species from a continent.

It started with fantasies that wolves might find their way into our most intimate lives like the dogs had. Wolves were supposedly bloodthirsty creatures of the ungodly wilderness that stalked folks who wandered too far from their village. Sometimes those bitten by wolves sprouted hair and claws before a month was out and howled in bedsheets of full-size moonlight. These werewolf tales perhaps originated after rare attacks by winter-starved or rabid wolves in Europe, which interestingly did transmit a disease that drove people wild and crazy (Fogleman, 1989). Whatever their origin, in an age where what was out in the woods mostly grew in human imagination and wild stories threw fuel on the fire, wolf hatred heated up American homes. Men stepped out doorways set deeper and deeper in the American West, ready to show another sort of fire to animals that threatened their precious game and livestock.

By the mid 20th century, virtually all grey wolves were gone from the lower 48 at the hands of what ultimately became a government-sanctioned campaign to exterminate the species. Protection under the Endangered Species Act of 1973 came too late to save. Undoubtedly, the slaughter that humanity’s fairy tales left behind them was bigger and badder than any wolf tails a rancher might spot amongst his cattle.

In the 1990s, wolves trapped in Canada were reintroduced to Yellowstone National Park and Idaho. Since, the species has significantly recovered, with 1900 grey wolves now living in Wyoming, Montana, Idaho, Washington, Oregon, California, and Colorado, while their numbers have reached 4200 in Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota (Williams, 2022).

Unfortunately, the delisting of grey wolves from the Endangered Species Act in 2017 has invited wolves’ persistent enemies to reignite a holocaust against them. For instance, the Wyoming Department of Game and Fish is allowing the killing of wolves with snowmobiles and by fire thrown into dens (Williams, 2022). Pups and nursing mothers have been incinerated alive. Idaho and Montana have put up bounties with the goal of killing 90% of their wolves (Williams, 2022). The slaughter extends into the Great Lake states.

It’s not hard to do the math when there were only around 6000 wolves in the United States before the new extermination campaign got fired off: Wolves may not be off the list of species endangered in the United States for much longer (though the IUCN misleadingly classifies the species as “Least Concern,” reflecting the gray wolves global stability) (Boitani et. al., 2023).

Figure 8: Current IUCN Red List Status of the grey wolf (Boitani et. al., 2023).

Ironically, evidence suggests that life in protected parks has made wolves less skittish around people and emboldened them to journey beyond the borders of safety. Hunting outside Yellowstone and wolf deaths per year have climbed from 2 to 3 in prior years to an unsustainable 24 in 2022 (Williams, 2022). Farther north in Canada, an aerial wolf extermination campaign began in 2015 to protect woodland caribou endangered in the face of forest fragmentation and resulting swells in wolf populations. British Columbia has set a goal of culling 80% of its wolf population to protect caribou (Morton, 2023). So there goes many of the grey wolves in Canada.

Wolves generally want to stay where their prey is best and there is no perceived risk to the pack. Culls of wolves in Canada’s fragmented forests could keep their populations from proliferating into more developed areas as competition between packs becomes too fierce. But the culls could also teach innately intelligent and calculating wolves that there is danger on the forest roads and cut blocks and inadvertently drive them to try their luck and provoke wolf hatred outside their prime habitat.

In trying to save caribou, conservationists may seriously frustrate efforts to protect grey wolves.

Saving Red Riding Hood

Big bad wolves aren’t so bad. Few species have such charismatic value to society, evidenced by the wolf art and photography that runs wild on social media. And there is surely something magical about hearing wolves’ howls rise into the night? Like mountain lions, wolves are also diminishing vehicle accidents on account of their preferred ungulate prey. Society should thank them, frankly, for saving car hoods (perhaps even invite the ghost of Prince to counter half-truths spoken in Little Red Riding Hood by singing about his little red corvette).

Finally, wolves make states a lot of money. Take the $1 million that each of Yellowstone’s wolves is estimated to bring the Wyoming economy in terms of money spend on hotels, shopping, and going out to eat (Williams, 2022). By comparison, one dead wolf earns a trapper or hunter a single whopping profit of around 200 bucks (Williams, 2022)!

Saving wolves largely comes down to preventing habitat loss. It entails the preservation of vegetative coverage that supports grey wolf prey, the defense of natural dens and dispersal corridors, and taking wolves out of the sights of the planet’s apex human predators.

Our most obvious wolf conservation goal, as it is with mountain lions, should be the continued protection of large areas of western North America. Nevertheless, if wolf populations in national parks become unsustainable, resistance to state-sponsored wolf extermination campaigns to mitigate depredation becomes just as critical a conservation concern as the general protection of western lands. This resistance can be accomplished through lobbying, public education efforts, as well as federal, state, local, and/or tribal grant programs that compensate farmers and ranchers for livestock losses. Such grant programs are already in place in Minnesota, Wyoming, and other states where the packs run, putting those dollars brought in by the wolves to good use. New grant programs should be organized by local communities interested in promoting their clear economic interests in protecting wolves and promoted to ranchers.

Wolf conservation is also tied to the collateral damage from other conservation concerns, specifically efforts to save caribou. A solution may involve the concept of triage, or the prioritizing of species that have a good shot at success rather species who have little chance of making it. As you might imagine, it’s a contentious debate whether or not species with the potential to do well in environments transformed by mankind should be deprioritized or even have their success punished for the sake of saving species like caribou, which seem to be holding on like leaves in the late fall.

The mental health of wolfpacks in their new prime territory and treatment of irrational wolf hatred is something society needs to support, for both wolves’ interests and our own. We must defend forests from over-fragmentation to protect wolves. We must protect wolves so that trees cut for timber or cleared by old age don’t get eaten down to barren antlers by ungulates and climate change doesn’t ravage our lives and economy. Your future electric sportscar will do better when the wolves also run silently through the forest. It’ll be protected from obstacles, like deer in the road, and you’ll know that its reduced carbon footprint is making a bigger dent in the sustainability crisis because future generations of forest are still breathing.

References:

- Collinge, Mark. 2008. Relative Risks of Predation on Livestock Posed by Individual Wolves, Black Bears, Mountain Lions, and Coyotes in Idaho. Proc. 23rd Vertebr. Pest Conf. (R. M. Timm and M. B. Madon, Eds.) Published at Univ. of Calif., Davis. 129-133. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3q40g86f

- Boitani, L.; Phillips, M.; and Jhala, Y. 2023. Canis lupus (amended version of 2018 assessment). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2023: e.T3746A247624660. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2023-1.RLTS.T3746A247624660.en. Accessed on 19 April 2024.

- Fogleman, Valerie M. 1989. American Attitudes Toward Wolves: A History of Misperception. Environmental Review, Vol 13, No. 1, pp 63-94. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3984536?seq=4

- Morton, Michelle. 2023. $10M spent on B.C. wolf cull, FOI documents reveal alongside details of shootings. CBS News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/10m-spent-on-b-c-wolf-cull-foi-documents-reveal-alongside-details-of-shootings-1.7065846. Accessed on 19 April 2024.

- Muhly, Tyler B.; Johnson, Cheryl A.; Hebblewhite, Mark; Neilson, Eric W.; Fortin, Daniel; Fryxell, John M.; Latham, Andrew David M.; Latham, Maria C.; McLoughlin, Philip D.; Merrill, Evelyn; Paquet, Paul C.; Patterson, Brent R.; Schmiegelow, Fiona; Scurrah, Fiona; Musiani, Marco. 2019. Functional response of wolves to human development across boreal North America. Wiley Ecology and Evolution. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/ece3.5600

- Accessed on 19 April 2024.

- Gables, Thomas. 2021. Wolf pack territory. International Wolf Center. https://wolf.org/wolf-info/factsvsfiction/economically-savvy-wolves-wolf-packs-choose-size-of-territory-based-on-the-costs-and-benefits/. Accessed on 19 April 2024.

- Sells, Sarah N.; Michell, Michael S.; Prodruzny, Kevin M.; Gude, Justin A.; Keever, Allison C.; Boyd, Diane K.; Smucker, Ty D.; Nelson, Abigail A.; Parks, Tyler W.; Lance, Nathan J.; Ross, Michael S.; Inman, Robert M. (2021). Evidence of economical territory selection in a cooperative carnivore. Proceedings of Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rspb.2021.0108

- Stricker, Heather K.; Gehring, Thomas M.; Donner, Deahn; Petroelje, Tyler (2019). Multi-scale habitat selection model assessing potential grey wolf den habitat and dispersal corridors in Michigan, USA. Ecological Modeling, Vol 397. https://www.fs.usda.gov/nrs/pubs/jrnl/2019/nrs_2019_stricker_001.pdf

- Wielgus, Robert B. and Peebles, Kaylie A. 2014. Effects of Wolf Mortality on Livestock Depredation. Plos One. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0113505

- Williams, Ted. 2022. America’s New War on Wolves and Why It Must Be Stopped. Yale Environment 360. Published at the Yale School of Environment. https://e360.yale.edu/features/americas-new-war-on-wolves-and-why-it-must-be-stopped.